3 billion BC : The origin of diamonds

Diamonds are considered one of the oldest materials on earth: 1 to 3.5 billion years old. Planet Earth is ‘only’ 4.5 billion years old.

100 million BC: Kimberlitic explosions

Diamonds are formed at the center of the earth. They only make it to the surface by coincidence, e.g. because of erupting volcanoes. The journey to the earth’s surface is not without its perils. Diamonds burn up in magma so rough diamonds need to be insulated inside a piece of kimberlitic rock to make it all the way up.

Ca. 400 BCE: The first Diamonds in India

The earliest known reference to diamonds is a Sanskrit manuscript, "The Lesson of Profit" (Arthasastra) by Kautiliya, 320-296 BCE.

"(a diamond that is) big, heavy, capable of bearing blows, with symmetricalpoints, capable of scratching (from the inside) a (glass) vessel (filledwith water), revolving like a spindle and brilliantly shining is excellent. That (diamond) with points lost, without edges and defective on one side is bad."

The very first diamonds were discovered in and around Indian rivers. People were afraid to cut them, fearing the stones would lose their ‘magical powers’. You were only allowed to polish them. The biggest diamonds were automatically claimed by the local rulers.

Diamonds were a valued material. Beads marked by diamond drills dating from the 4th century BCE have been found in ancient sites in Yemen. Back then, the Sanskrit name for Diamond was Vajra, thunderbolt or Indrayudha, Indra's weapon.

It is difficult to trace back the history of diamonds in the written word because of the many names they have carried. The word diamond comes from the Greek word Adamas = the unbreakable. Plato’s student, Theophrastus, ca. 372--322 BCE, referred in his "De lapidibus" or "On Stones" the word Adamas to emery, a rock containing corundum, the hardest mineral after diamonds. Pliny the Elder wrote in his encyclopedia "Historia naturalis", 77-79 CE:

"The substance that possesses the greatest value, not only among precious stones, but of all human possessions, is adamas; a mineral which for a long time, was known to kings only, and to very few of them...These stones [diamonds] are tested upon the anvil, and will resist the blow to such an extent as to make the iron rebound and the very anvil split asunder."

"These particles are held in great request by engravers, who enclose them in iron, and are enabled thereby, with the greatest facility, to cut the very hardest substances known."

Ca. 1300: The first Diamond Trading Routes to Europe

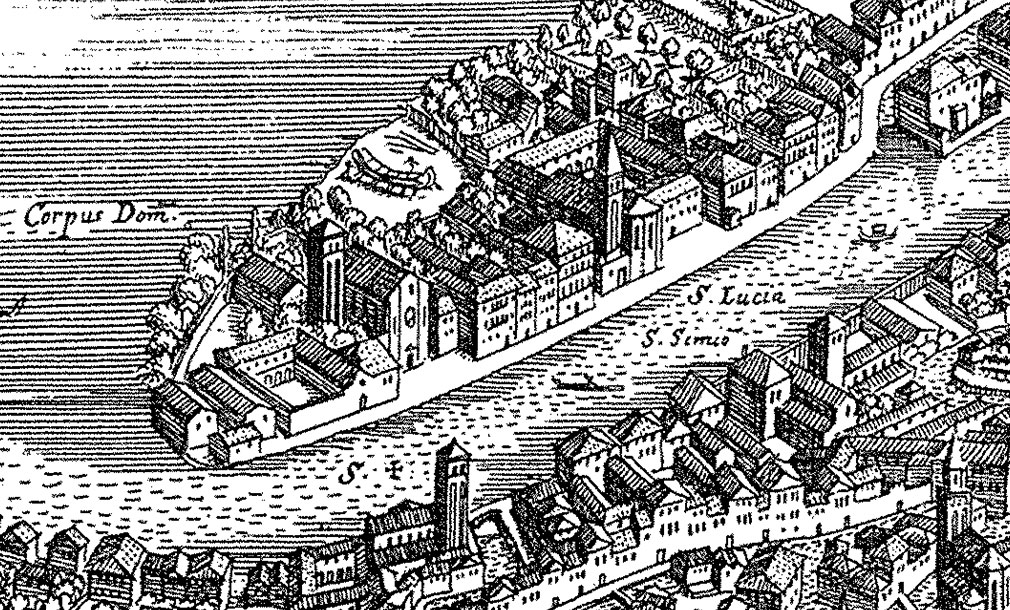

Diamonds begin to appear in European jewellery in the 13th and 14th centuries. The earliest European diamond trading capital was Venice, where the first attempts to polish the natural faces and flaws of the diamond originated sometime after 1330. By the end of the 14th century, the diamond trade route continued to Bruges and Paris, and later to Antwerp. When Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to the Orient around the Cape of Good Hope in 1499, he gave Europeans the opportunity to reach India directly and to avoid problems of the overland route. Goa became the Portuguese trading center, and a diamond route was developed from Goa to Lisbon to Antwerp, allowing a yearly import of 1000 to 2000 carats until 1725.

The oldest document proving the existence of the diamond trade in Antwerp dates from 1447. 1475 brings us the first diamond polishing wheel infused with a mixture of olive oil and diamond dust: the Scaif, invented by Lodewyk van Berken. With it comes the concept of absolute symmetry in the placement of facets. In 1565 Benvenuto Cellini describes for the first time the diamond polishing equipment.

Initially, diamonds were only worn by male rulers. After a while, other prominent men also started wearing them. Rubens, the famous Flemish Baroque painter, owned and wore several diamonds. It was only much later, starting in the 15th century, that women also started wearing diamonds. The trendsetter in that respect was Agnès Sorel, the mistress of the French king Charles VII. She was given a diamond by her lover.

The first engagement ring with a diamond symbolizing eternal love was given to Maria of Burgundy by Maximilian of Austria in 1477. The entire world followed in their footsteps.

In 1448 the first Antwerp cutter became known. “Wouter Pauwels – diamantslyper”, that’s what you can find in the archives of the brotherhood of ‘Onze Lieve Vrouw Lof’. Wouter probably wasn’t the first Antwerp diamond cutter, but he’s the first one whose name was registered.

Not many cities could ‘cut it’ compared to Antwerp in the 16th century. It was the world’s biggest trade center, so its port welcomed 40% of the world’s trade, with a starring role for the diamond industry. The city has been able to hold on to its top position in the global diamond trade ever since.

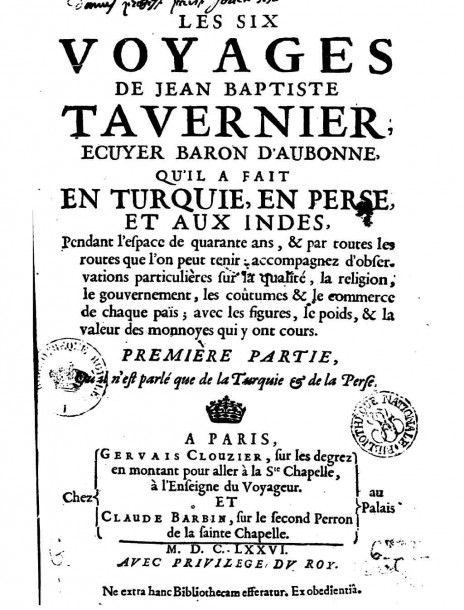

17th century: Jean-Baptiste Tavernier

The intrepid French trader, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, was the first European who obtained permissions to visit the Indian diamond fields. In his “Les six voyages de Jean-Baptiste Tavernier” he tells about the mines near Golconda, famous for its precious stones, and thoroughly describes larger diamonds and stories or myths about famous diamonds. Tavernier’s most famous find was a remarkable blue diamond which is known today as the Hope Diamond. He also brought home 20 enormous diamonds, some of which he sold to the French king, Louis XIV in Versailles. The Tavernier quay at the Antwerp river the Scheldt was named after him.

In 1725 new diamond deposits were discovered in Brazil, and production was significantly enlarged. Yearly imports to Lisbon from 1000-2000 to 100.000-200.000 carats. These volumes remain approximately the same until 1867 when secondary deposits were discovered in South Africa. In 1870, the first primary deposits are found in Kimberley. From there rough diamond production constantly grows: 1877 = 1,8 million carats; 1892 = 3 million carats; 1913 = 6 million carats. In 1949 Russian deposits are found in Siberia, adding 15 million carats to world production.

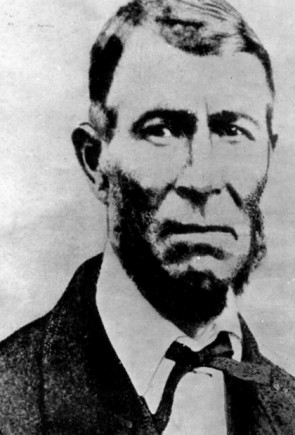

Two simple farmers, but everybody knows their name: Johannes Nicolaas and Diederik Arnoldus De Beer. When they bought their South African farm ‘Vooruitzicht’ in 1865, they had no idea it would be a diamond mine.

In 1871, they found a rough 83.5-carat diamond. The brothers sold their land for 6,800,000 British pounds: a huge amount, but the De Beers diamond mine that was founded on their courtyard delivered diamonds worth tens of millions more.

The ‘Cullinan’ diamond weighed in at 3,106 carat. The diamond was named after the owner of the mine and split into 9 cut stones: Cullinan I to IX. All 9 stones were donated to the British royal family.

1919: Antwerp local Tolkowsky refines the ‘brilliant’ cut

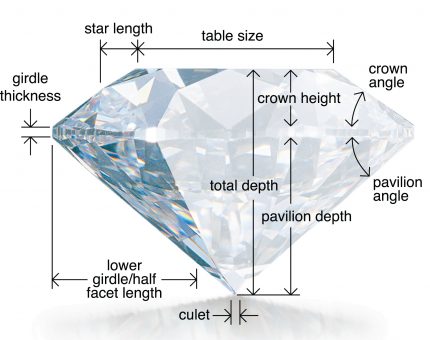

No less than 80% of all colorless diamonds are brilliant-cut. This cut consists of 57 planes or facets and was refined by Antwerp local hero Marcel Tolkowsky. True Antwerp craftsmanship!

1944: Recovery

Jewish diamond cutters and traders that were not able to find refuge, were deported to concentration camps during World War II. Of the 1,645 members of the Antwerp Diamond Bourse, only 355 remained. Each year, the shoah is remembered with a minute of silence.

1944: Bounding Diamond Office

The Belgian and British governments founded the ‘Diamond Office’ to encourage Jewish ‘diamantaires’ to return to Antwerp soon after the Second World War.

1960: Capital of trade and processing

Up until the beginning of the 1970’s, most of rough diamonds that were traded in Antwerp, were also cut there. Some of the cutting trade has moved to lower income countries since then. Most large and complex stones are still cut in Antwerp though.

2002: No to conflict diamonds

In 2002, the Kimberley-certificate is implemented to curb conflict diamond trading and was implemented in 2003.

2014: Record year for Antwerp diamond trade

The Antwerp diamond trade booked a record revenue in 2014. More than 227 million carat rough and cut diamonds were traded, estimated at 58 billion dollars. This makes diamonds one of Belgium’s most important export products. Within one square mile, you’ll find about 1,700 diamond traders hard at work. In total, 32.600 people are directly or indirectly working for this brilliant industry.

Today

Today’s diamond market presents producers with four major challenges: reserve replenishment, environmental challenges, increasing social awareness, increasing pressures on operating costs

Reserve replenishment

There are few known major underdeveloped diamond sites, and no major discoveries have been made over the past two decades. As a result, the cost of finding new, economically recoverable deposits is rising.

Environmental challenges

Increasing public awareness of environmental topics has had direct impact on the mining business. Producers are under pressure to make effective use of energy and reduce emissions. They must also focus on waste management to increase recycling and control water consumption, a task complicated by the fact that most important production sites are located in water-scarce areas. And mining’s impact on biodiversity and ecosystems in general is an issue.

Social awareness

Producers are paying increasing attention to local communities in areas of production, resulting in direct and indirect impacts on output. Beneficiation programs are meant to support economic development and boost employment in diamond-producing countries by setting up local cutting and polishing operations. Such businesses were set up in Africa in recent years, and there is a discussion of developing a Russian cutting and polishing industry under ALROSA’s, Russian, leadership. Indirect impacts are visible in producers’ involvement in local communities outside their core mining activities. This involvement often takes the form of financing or developing social infrastructure in mining areas.

Increasing pressure on operating costs

Consistent with the mining industry as a whole, diamond producers are facing rising costs for inputs such as labor and energy, as well as projects whose increasing technical challenges translate to higher operating costs.

Confronting mounting challenges that are not unique to the diamond industry but rather representative of the entire mining sector, producers must make significant investments in new technology and operating efficiency to sustain the diamond mining industry in the medium and long term. (Global diamond Report 2014)